O’Hagan Meyer’s Design Professional Team is proud to present our latest newsletter, crafted specifically for architects, engineers, and other design professionals. In this edition, we tackle three critical risk management topics to help safeguard your practice:

-

Client Selection Red Flags: Learn how to spot potential issues early to make more informed decisions and avoid problematic client relationships.

-

Arbitration vs. Trial: Discover the pros and cons of arbitration as a dispute resolution method, and find out when it might—or might not—be the right choice.

-

The “Sunset Trap”: Understand how indemnity clauses can extend liability far beyond expected legal deadlines and how to draft contracts to mitigate this risk.

Our goal is to provide practical insights and guidance to help you navigate legal challenges and build a more resilient practice. We hope you find these articles valuable and encourage you to reach out with any questions or feedback.

Important Considerations in Client Selections

By: James W. Walker, Esq., Brandon Sieg, Esq., and Enaita Chopra, Esq.

Design professionals, like all professionals (including lawyers), delight when the phone rings with a prospective new client on the line wanting to hire you for a new project. However, any lawyer who regularly represents design professionals has stories about projects that went south and ended up in litigation almost entirely because red flags at the commencement of the engagement were ignored.

While no project is completely without risk, managing risk from first contact with a new client is as essential as managing risk during the engagement itself. Some risks may warrant walking away from the engagement altogether; others may be appropriately managed through thoughtful contract negotiation. This article is not intended to give advice on which new clients or projects to take on or what contract terms would be useful to manage risk. Rather, it is intended to flag issues that will allow you to make better business decisions within your risk profile and tolerance.

Below are some circumstances to consider when deciding if you want to work with a prospective client at all or with the client on a particular project.

- Client’s project experience. This may be the most important consideration. When engaging in a project, you should consider if the client is inexperienced generally or inexperienced with projects of the type, scale, cost, or scope proposed. Some factors that can help gauge their inexperience include: (i) the client has only a vague notion of desired program; (ii) the client has unrealistic expectations for budget, fees and/or schedule; (iii) the client is chasing the lowest bid for design services; and (vi) the client is in poor financial condition or has no clear plan to pay for/finance design and construction. If you are unfamiliar with the client’s experience, ask questions of the client and/or others who have worked with the client in the past. There is always a first time, but knowing it’s a first time can help set up the contracts appropriately or provide a basis for declining the work.

- Client leadership structure. How the client is structured and how they manage their business can influence the relationship with the project team. Consider the following:

-

-

- Is Client management and decision making is divided or unclear? Churches, some government entities, condo associations, partnerships, etc. can have organizational issues where it is difficult to know who is making decisions you can count on. Seek clarity on who speaks for the client for purposes of contract administration.

- Does Client communicate timely, effectively, and consistently? The lack of a clear chain of command and timely decision making can increase the cost of the work and the risk of a claim. Decisions can be delayed, countermanded, or unclear.

- Is the client reluctant to sign a written agreement? This could reflect lack of authority within the organization or naivete. Either way, it’s a red flag.

- Does the client have a project manager or other representative with sufficient experience to be an effective liaison with the client?

- Are there other stakeholders beyond your contract counterparty who will expect to have decision-making authority? Examples could be outside investors of an entity that, on paper, looks to be small. Examples could also include large corporate families that create a special purpose entity to run this specific project. Red flags might include proposed indemnity terms in the contract requiring you to indemnify a web of people or entities with whom you are not familiar.

-

- Client’s other business experience. History can be a good teaching experience. Investigate whether the client routinely falls behind on paying bills, has a history of claims or litigation, or a negative reputation with your peers or in the business community generally.

- Specializations. Do you have expertise in the project type:

-

-

- Is the project of a type that carries higher risk relative to fee, such as a church, custom single family residential, highly-specialized function for the space, condominiums, or charitable organization?

- Does the project type carry a high subconsultant discipline-specific risk? For example, does the project include tunnels bridges or other atypical structural elements, urban infill with challenging civil and infrastructure design, student housing or hotels with atypical MEP demands, etc.? As the prime A/E, are you comfortable taking on the risk, and have you selected consultants well-suited to help you manage the risks?

- Is the project type, scale, scope, or location outside your experience and comfort zone? If so, should you pass or build in time and expense for risk mitigation.

-

- Miscellanous. Other considerations include:

-

-

- A client who has pre-selected a general contractor and the selected contractor has any of the issues above.

- A client who is asking you to take over a project after terminating a prior design professional’s contract. Be very careful in particular if the potential client suggests you continue developing the design prepared by the terminated professional, which might implicate copyright protection and other legal issues.

- A client who demands that the contract include warranties, broad indemnity, or other unusual risks to the A/E.

- A client who wants to assign duties to design professional that do not belong in a design service agreement, e.g., responsibility for hazardous materials, testing obscure or specialty equipment, purchasing or supplying equipment or furnishings.

-

Please contact your O’Hagan Meyer attorney or the authors of this article if you have any further questions.

Is Arbitration Right for You?

By: James W. Walker, Esq. and Enaita Chopra, Esq.

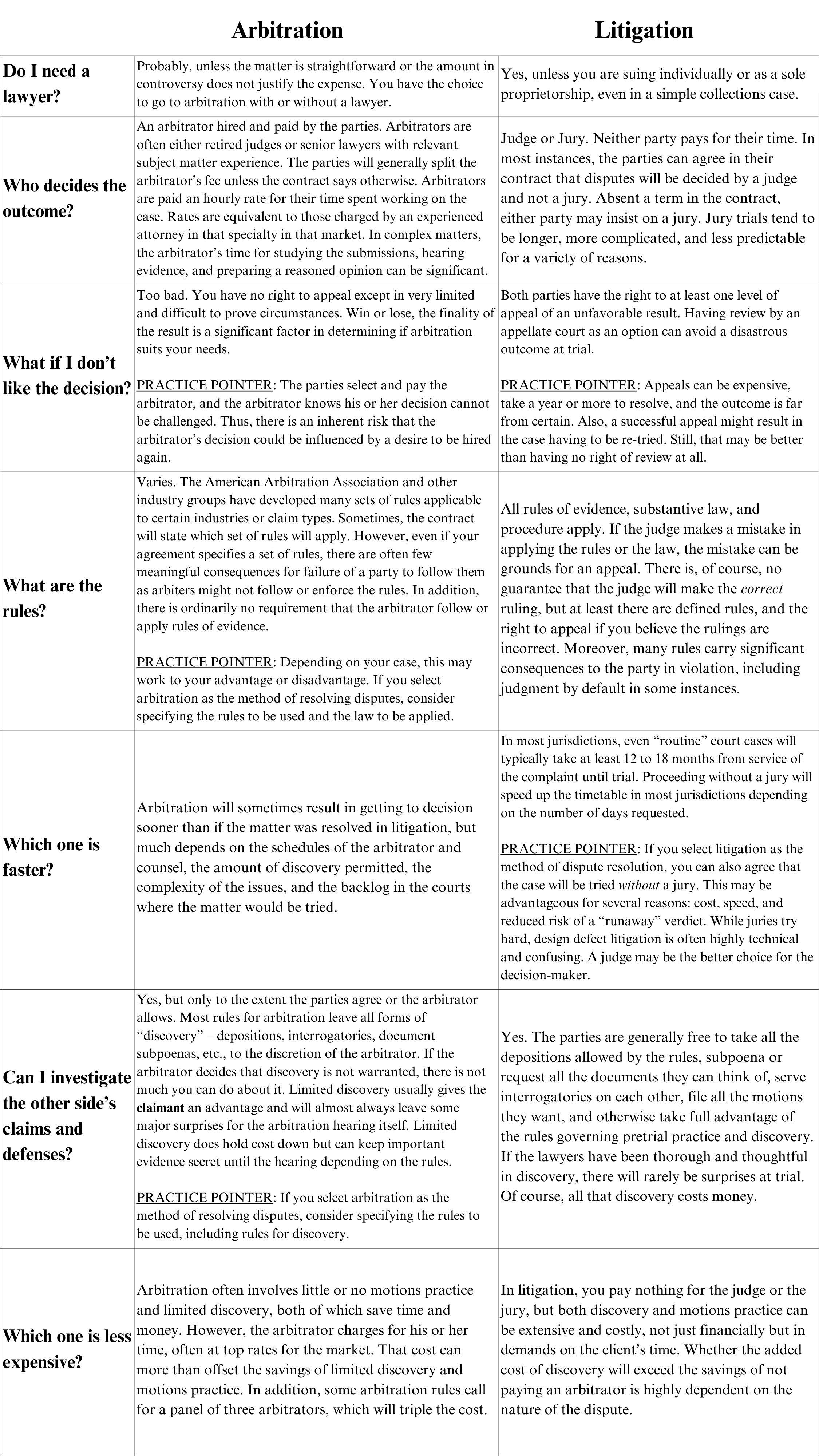

One common provision in design services contracts is a requirement to resolve disputes with binding arbitration. One major reason for including such provisions is the notion that arbitration is a more efficient and less expensive means to resolve disputes before a technically proficient arbitrator than going to court. While this is certainly true in some instances, it is far from universally true.

What are the Differences?

Additional Practice Pointers

- Even if you have agreed to arbitration, the parties can always mutually agree to waive that requirement.

- Before accepting or rejecting an arbitration provision in a contract, make certain that you understand what claims are going to be arbitrated. Most arbitration provisions are written broadly, so virtually any dispute between the parties will go to arbitration. Arbitration agreements might even prevent you from asking a court to decide what claims you are required to arbitrate, forcing you to let the arbitrator decide that question as well. However, the parties are free to craft an arbitration agreement that is narrower in scope. For example, the parties can agree that arbitration will only be required for certain types of disputes (e.g., claims for the design professional’s unpaid fees, change orders disputes, etc.) or that only claims up to an agreed maximum amount will be covered by the arbitration clause.

- Consider drafting the arbitration term to require that certain disclosures be made in connection with a demand for arbitration or that certain types of discovery (such as depositions) be allowed. This will help eliminate surprise and the risk that the arbitrator will not permit discovery, but the additional discovery will add to the cost of arbitration.

- Agreeing to arbitrate does not rule out mediation. Consider including language in the contract that requires mediation before moving on to the chosen method of binding dispute resolution, i.e., arbitration or litigation.

- Whether arbitration or litigation is the better option may well depend on the jurisdiction in which litigation would occur for a particular project, either because the substantive law is less favorable or the jury pool less desirable.

- Keep in mind that arbitration is private, while litigation is a matter of public record. The public can review the complaint and any other document filed with the court, and the trial is open to the public. If you use arbitration, however, the details of your dispute will remain private.

- If you select arbitration, then you and your opponent will be able to select who arbitrates your dispute. So if you have a complex construction issue, you can select an arbitrator who holds at least basic knowledge about the construction industry and related litigation. If you go to court, then your judge’s background is luck of the draw, meaning you case could potentially be assigned to a newly appointed judge without construction litigation experience.

Arbitration can be a useful, sometimes less expensive means for resolving contract-based disputes before decision-makers with subject matter expertise, but this method of dispute resolution also has its drawbacks and may not be well suited for every contract, every project, every claim, or every client. Before including an arbitration provision in a professional services contract, carefully consider the advantages and disadvantages and whether arbitration is right for that particular contract. Also, it is always prudent to consult an attorney for advice on which dispute resolution option is best for you.

Sunset in Repose…

By: James W. Walker, Esq. and Maxfield B. Daley-Watson, Esq.

Who doesn’t enjoy a beautiful sunset, right? Signals the end of another day gone forever. But what if the sun never sets?

Statutory Sunsets. Statutes of limitation and repose are legal “sunsets” marking the time after which construction and design professionals can no longer be sued for deficiencies in their work or services. Most design and construction professionals in Virginia know that Virginia has a five-year statute of limitations applicable to lawsuits for breach of a written contract and a five-year statute of repose applicable to lawsuits for personal injuries, wrongful death and property damage.[1] One might conclude that the “sunset” on any exposure to liability on a construction project occurs five years and a day after the project is completed. Indeed, many firms tie their file retention policies to the five year anniversary of project completion. However, depending on the terms of your contract, Virginia law leaves open a significant hole in the “sunset” provided by the statutes of limitations and repose.

Consider this scenario: Schiff-TEE Enterprises, a mining company, hired Casey Jones Engineering to design a coal slurry impoundment near a mountaintop mine. Schiff-TEE hired Damwright Construction to construct the impoundment. In 2005, Schiff-TEE entered into standard AIA contracts with both Damwright and Casey Jones –an A201 with Damwright and a B141 with Casey Jones. The project was completed in April 2009[2]. In May 2017, the impoundment failed, sending millions of gallons of slurry into the small mining town in the valley below. No one was hurt, but many homes and businesses were damaged.

Shortly after the incident and eager to avoid a publicity nightmare, Schiff-TEE agreed to pay hastily negotiated fines to state and federal regulatory agencies and settle claims for damage to homes and businesses. Schiff-TEE made all payments in July 2018. In June 2019,[3]Schiff-TEE filed suit against Casey Jones and Damwright seeking to be reimbursed. Schiff-TEE alleged that the dam failed because of a combination of shoddy construction by Damwright and poor design by Casey Jones.

Legal. Under Virginia’s five-year statute of repose, potential exposure of Damwright and Casey Jones to townspeople, for personal injury and property damage claims, ended in April 2014—five years after the project was completed – even though the dam had not yet failed. Similarly, Schiff-TEE’s right to sue Damwright and Casey Jones for traditional breach of contract claims expired at the same time. However, both contracts had provisions by which Damwright and Casey Jones agreed to “indemnify” or reimburse Schiff-TEE for amounts Schiff-Tee paid to others on account of A/E or general contractor negligence.

Here is the problem: First, the five-year statute of limitations to bring a claim seeking indemnity, based on an express indemnity provision in a contract, does not start to run until the party seeking reimbursement (Schiff-TEE) has paid the injured party (government and town people). So even though Damwright and Casey Jones had completed their work in April 2009 and the dam failed 2017, the five year limitations clock for Schiff-TEE to bring an indemnity claim did not start until July 2018 when it paid out settlements. Thus, the suit Schiff-TEE filed against Damwright and Casey Jones for indemnity is timely from a limitations perspective. Second, the 4th Circuit Court of Appeals has opined that Virginia’s five-year statute of repose does not apply to a lawsuit seeking to enforce a written indemnity provision.[4] Even though the statute of repose precludes townspeople from suing Damwright or Casey Jones directly, the statue of repose would not preclude Schiff-TEE from demanding reimbursement for its payments to townspeople.

Damwright and Casey Jones may well have many excellent defenses to Schiff-TEE’s claims of negligence, but winning on those defenses would likely involve expensive and time-consuming litigation. Ultimately, any litigation could come down to a jury trial and seven randomly selected citizens with very little understanding of the complex subject matter. This is risky and expensive. But there are solutions.

Solution. All standard AIA design contract documents published since 2007 include this provision:

The Owner and Architect shall commence all claims and causes of action, whether in contract, tort, or otherwise, against the other arising out of or related to this Agreement in accordance with the requirements of the method of binding dispute resolution selected in this Agreement within the period specified by applicable law, but in any case not more than 10 years after the date of Substantial Completion of the Work. The Owner and Contractor waive all claims and causes of action not commenced in accordance with this section.[5]

This is a contractual “sunset” provision. Remember those dates? Construction complete in April 2009 and the indemnity lawsuit not filed until July 2019? In our scenario, if Damwright and Casey Jones had included this standard AIA sunset provision, they would been able to bring Schiff-TEE’s lawsuit to an early and inexpensive end.

Practice Pointers. Even if you choose not to use AIA contract documents, there is no reason why you cannot or should not incorporate this important protection into your own contract forms. Also, there is no magic to the ten year “sunset.” The drafters of the AIA documents selected a ten year “sunset” as its balance of the Owner’s desire to have a reasonable time for latent deficiencies to cause a problem and the Contractor/Architect’s desire for a time certain beyond which he will not be exposed to claims from completed work. Since Virginia has already adopted five years as the statutory “sunset” for repose and for suits to enforce written contracts, we usually recommend a five-year sunset for our Virginia A/E’s as a reasonable and logical time for a contractual sunset provision for Virginia projects. However, the date for sunset is negotiable, and having at least some agreed date is better than no sunset at all. Otherwise, the sun never sets on an indemnity claim.[6]

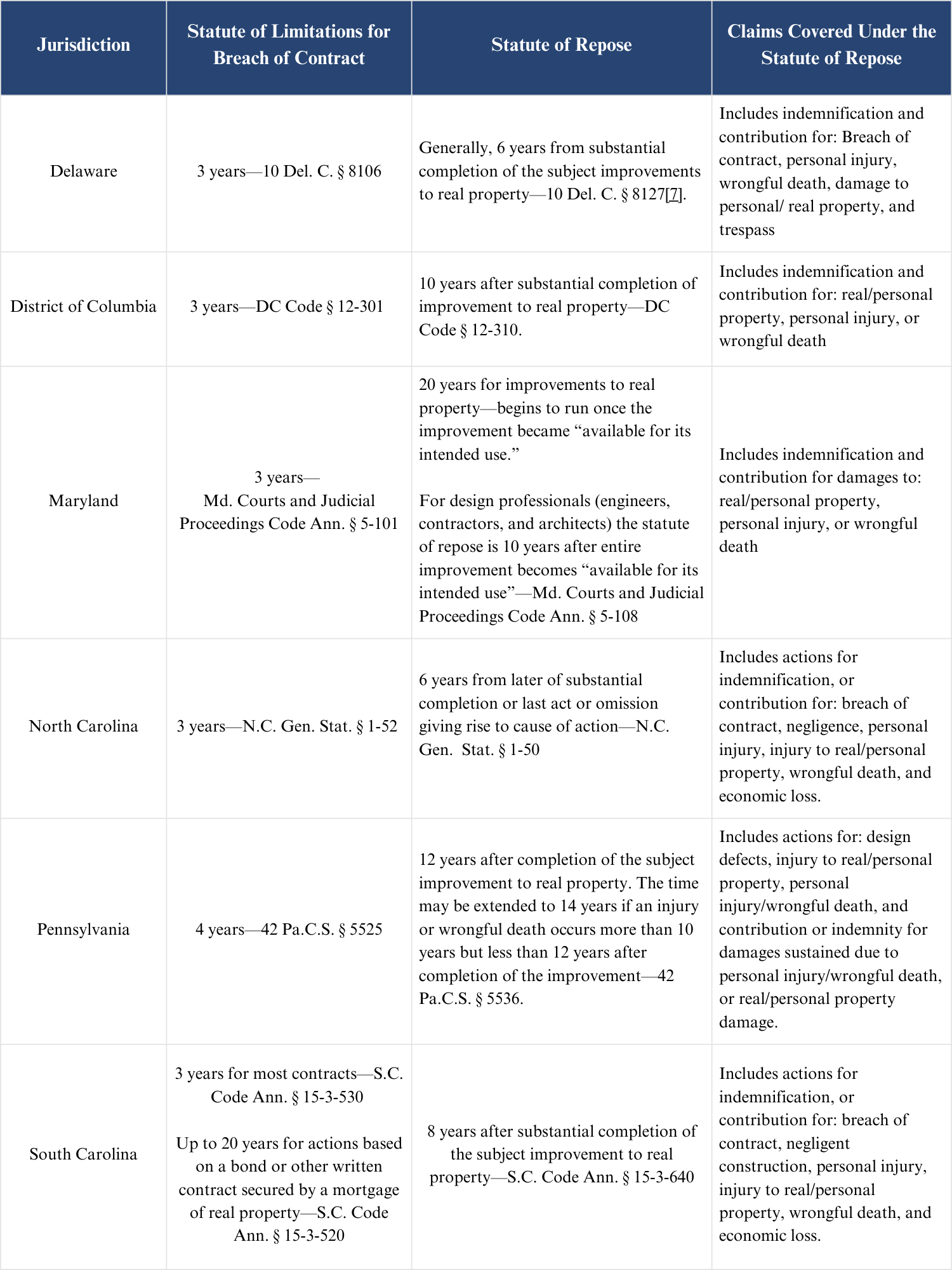

Looking Beyond Virginia. The example above places specific focus on Virginia’s statute of repose and its unique “sunset trap.” However, including sunset provisions in design services agreements is useful for design professions wherever they may practice. The table below provides a brief snapshot of the statutes of repose and limitations for several other jurisdictions along the eastern seaboard.

Please contact your O’Hagan Meyer attorney, or the authors of this article, if you have any further questions.

[1] Statutes of limitation and repose vary widely from state to state, both in terms of duration and scope. This article addresses a uniquely Virginia issue.

[2] Remember this date.

[3] Remember this date, too.

[4] Lone Mt. Processing, Inc. v. Bowser-Morner, Inc., 94 Fed. Appx. 149, 158 (4th Cir. 2004); See also, Va. Code §8.01-249(5)

[5] This is the §8.1.1 of the B101. Section 13.7 of the new A201 is identical except the term Architect is changed to Contractor. The AIA updated the above cited language in 2017, but it remains substantively the same.

[6] The author had a matter not long ago where the owner brought an indemnity claim against the A/E almost 25 years after the project was completed. Because there was no sunset provision in the contract and the two statutory sunsets didn’t apply, the A/E had to defend on the merits.

[7] 10 Del. C. § 8127, contains multiple provisions that might trigger or delay the running of the six-year statute of repose. To that end, adoption of the standard AIA sunset language could be particularly beneficial for design professionals who anticipate doing work in Delaware.

To learn more about our A&E team, click here.