O’Hagan Meyer’s Design Professional Team is excited to introduce our new newsletter tailored specifically for architects, engineers, and other design professionals. As professionals who shape the built environment, your work presents unique challenges and opportunities. Through this newsletter, we aim to share insights, legal updates, and practical tips to support your projects and protect your business. Whether navigating complex contracts, mitigating risks, or staying ahead of industry trends, we’re here to help you build a stronger foundation for success.

Why Design Professionals Should Care About Consequential Damages

By: Jack Meyer, Associate

Design professionals often have (or request to have) waiver of consequential damages provisions in their contracts. But what are consequential damages and why should design professionals care if they are waived? In short, consequential damages are damages that do not flow directly and immediately from a design professional’s alleged wrongful act, but rather result indirectly from the act. For example, a party may allege that delays by an architect resulted in a hotel being unable to open during the summer travel season, causing lost profits. By way of further example, an owner could allege that defects in its building resulted in reputational harm and loss of future business opportunities.

Design professionals often have (or request to have) waiver of consequential damages provisions in their contracts. But what are consequential damages and why should design professionals care if they are waived? In short, consequential damages are damages that do not flow directly and immediately from a design professional’s alleged wrongful act, but rather result indirectly from the act. For example, a party may allege that delays by an architect resulted in a hotel being unable to open during the summer travel season, causing lost profits. By way of further example, an owner could allege that defects in its building resulted in reputational harm and loss of future business opportunities.

In other words, consequential damages open a party up to liability wholly out of proportion to the cost of repairing the actual damage. Unlike direct damages which are much narrower in scope and only include those damages which naturally flow from a party’s wrongful acts or omissions, consequential damages can be much broader. Because consequential damages do not directly result from the breach, they can often be unforeseeable to the parties at the time the contract was signed.

In order to avoid such expansive liability, any contract language making a party liable for consequential damages should be removed. Further, you should specifically include a clause in the contract stating that you are not responsible for consequential damages. An example of such language is provided below:

Notwithstanding any other provision of this Agreement, and to the fullest extent permitted by law, neither the Client, nor the Consultant, nor their respective officers, directors, partners, employees, contractors, or subconsultants shall be liable to the other or shall make any claim for any incidental, indirect, or consequential damages arising out of, or connected in any way to the Project or to this Agreement. This mutual waiver of consequential damages shall include, but is not limited to, loss of use, loss of profit, loss of business, loss of income, loss of reputation or any other consequential damages that either party may have incurred from any cause of action including negligence, strict liability, breach of contract and breach of strict or implied warranty.

Doing so can hopefully avoid the risk of liability for significant damages that cannot be eliminated at the time of contract.

The Impact of FTC’s Final Rule on Design Professionals

By: Maggie Nance, Associate

On April 23, 2024, the United States Federal Trade Commission voted 3-2 to finalize and promulgate a ban on non-compete agreements between employers and employees/independent contractors. While two legal challenges to the ban have already been successful in staying its implementation, if the stay is lifted, the ban could significantly impact design professional’s employment agreements.

The FTC non-complete ban provides that it is an unfair method of competition for employers to enter into non-compete agreements with workers on or after the ban’s effective date. With respect to non-compete agreements entered into before the date the ban takes effect, the rule adopts a different approach for senior executives than for other workers. For senior executives, existing non-compete agreements can remain in force. In contrast, for non-senior executives, existing non-compete agreements are not enforceable after the effective date of the ban. the final Senior executives are defined as workers earning more than $151,164 a year and who are in a “policy-making position.” Once effective, the new rule would require all employers across the country to notify their employees that any current non-compete provisions for non-senior executives are no longer enforceable.

The FTC non-complete ban provides that it is an unfair method of competition for employers to enter into non-compete agreements with workers on or after the ban’s effective date. With respect to non-compete agreements entered into before the date the ban takes effect, the rule adopts a different approach for senior executives than for other workers. For senior executives, existing non-compete agreements can remain in force. In contrast, for non-senior executives, existing non-compete agreements are not enforceable after the effective date of the ban. the final Senior executives are defined as workers earning more than $151,164 a year and who are in a “policy-making position.” Once effective, the new rule would require all employers across the country to notify their employees that any current non-compete provisions for non-senior executives are no longer enforceable.

At this stage, it remains unknown if and when the non-compete ban will take effect. In the meantime, authority to regulate post-employment competition by employees will remain with the states, and design professionals and design firms should continue to monitor state-by-state laws and state court decisions to ensure compliance with all applicable state restrictive covenants.

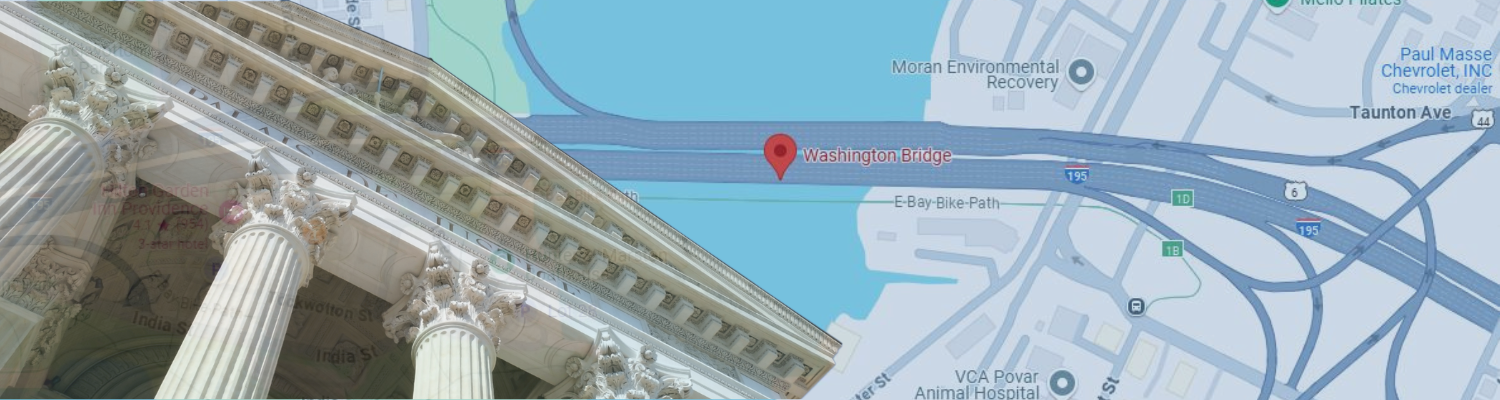

Bridge Failure Complaint Raises Fiduciary Duty

Claim Against Design Professional

By: David J. Scriven-Young, Senior Counsel

Breach of fiduciary duty claims, which are based on special relationships outside of typical business activities, are rarely made against design professionals. However, a recent complaint against a design professional relating to a bridge failure raises such a claim, which might have broad implications for the industry.

The claim, filed in Rhode Island Superior Court in State v. AECOM Technical Services, Inc., involved the emergency closure of the westbound span of the Washington Bridge, a critical piece of highway infrastructure that carried 90,000 vehicles a day. The bridge had an unusual design composed of eighteen spans of various structural types, including post-tensioned cantilever beams. In 2022, a $78 million design-build contract for the bridge’s rehabilitation and redevelopment began construction. This project would have included expanding the capacity of the bridge, reducing congestion, and installing a new off-ramp. The project stalled, in December 2023, when inspectors found a number of the steel tie-down rods had fractured and that there was extensive deterioration in the post-tensioning system in the cantilever beams. These structural conditions required the immediate closure of the bridge and made the rehabilitation of the bridge economically and structurally unfeasible. Thus, complete replacement at the cost of hundreds of millions of dollars was required.

As a result, the State of Rhode Island filed an action against thirteen companies that were involved in earlier inspections of the bridge or were involved in the abandoned rehabilitation project, including AECOM Technical Services Inc. AECOM had been selected and entered into a contract with the State for design services for the rehabilitation project. It also provided a technical evaluation report for the bridge and construction plans that, according to the State, failed to recognize or address critical elements of the bridge’s structural safety and integrity.

The State’s claims against AECOM sound in breach of contract, negligence, and breach of fiduciary duty. In that last count, the State alleges that AECOM held itself out to the State as a trusted expert in professional engineering, consulting, construction, and design, citing AECOM’s bid materials. The State alleges that it reasonably and justifiably relied on that expertise and that, when AECOM entered into its contract with the State, AECOM assumed and owed the State fiduciary duties that were eventually breached.

Breach of fiduciary duty claims are rare in complaints against design professionals, but can have significant implications when they are asserted. Generally, a fiduciary duty exists in business relationships where there are asymmetries of power between the parties in the relationship such that the client has to rely on the professional’s expertise. It is an affirmative duty from the professional to the client and requires the professional exercise the highest duty to care and a duty of loyalty to the client. Such claims can also be more powerful than contract claims because clients may seek disgorgement of funds paid to the professional during the period of the breach.

When faced with a breach of fiduciary claim against a design professional, most courts have ruled that a fiduciary relationship does not exist, even when the design professional has superior knowledge and expertise, because the business relationship was one that did not impose on the design professional the level of loyalty or invoke in it the kind of trust that characterizes a fiduciary relationship. Nevertheless, some courts have allowed fiduciary claims to proceed when design professionals (1) fail to provide advice on problems they knew or should have known about, (2) fail to represent their clients’ interests in dealings with contractors, or (3) have a conflict of interest, such as a financial relationship with a contractor, that was not disclosed.

Consistent with these principles, Rhode Island alleges that AECOM should have known about the critical problems facing the bridge based on the inspections it performed and its expertise in engineering transportation solutions. Whether Rhode Island’s claims will survive, however, remains to be seen.

To learn more about our A&E team, click here.